-

在线学习设计(二);The Role of Interaction in Online Learning

普通类 -

- 支持

- 批判

- 提问

- 解释

- 补充

- 删除

-

-

Defining and Valuing Interaction in Online Learnin

Communication technologies are used in education to enhance interaction between all participants in the educational transaction. However, although interaction has long been a defining and critical component of the educational process and context, it is surprisingly difficult to find a clear and precise definition of this concept in the education literature. In popular culture, the use of the term to describe everything from toasters to video games to holiday resorts further confuses precise definition. I have discussed the varying definitions of interaction at length in an earlier paper (Anderson, 2003), and so I will here simply accept Wagner’s (1994) definition of interaction as “reciprocal events that require at least two objects

and two actions. Interactions occur when these objects and events mutually influence one another” (p. 8).

Interaction (or interactivity) serves a variety of functions in the educational transaction. Sims (1999) has listed these functions as allowing for learner control, facilitating program adaptation based on learner input, allowing various forms of participation and communication, and acting as an aid to meaningful learning. In addition, interactivity is fundamental to creation of the learning communities espoused by Lipman (1991), Wenger (2001), and

other influential educational theorists who focus on the critical role of community in learning. Finally, the value of another person’s perspective, usually gained through interaction, is a key learning component in constructivist learning theories (Jonassen, 1991), and in inducing mindfulness in learners (Langer, 1989). Interaction has always been valued in distance education, even in its most traditional, independent study format. Holmberg (1989) argued for the superiority of individualized interaction between student and tutor when supported by written postal correspondence or by real-time telephone tutoring. Holmberg also introduced us to the idea of simulated interaction that defines the writing style appropriate for independent study models of distance education, programming that he referred to as “guided didactic interaction.” Garrison and Shale (1990) defined all forms of education (including that delivered at a distance) as essentially interactions between content, students, and teachers. Laurillard(1997) constructed a conversational model of learning in which interaction between students and teachers plays the critical role.

As long ago as 1916, John Dewey referred to interaction as the defining component of the educational process that occurs when the student transforms the inert information passed to them from another, and constructs it into knowledge with personal application and value (Dewey, 1916). Bates (1991) argued that interactivity should be the primary criterion for selecting media for educational delivery. Thus, there is a long history of study and recognition of the critical role of interaction in supporting, and even defining, education.

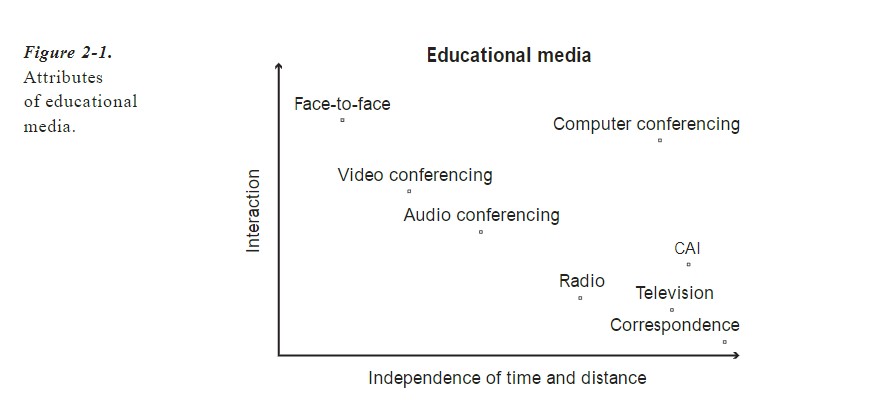

The Web affords interaction in many modalities. In Figure 2-1,we see the common forms of media used in distance education charted against their capacity to support independence (of time and place) and their capacity to support interaction. It can be seen that, generally, the higher and richer the form of communication, themore restrictions it places on independence.

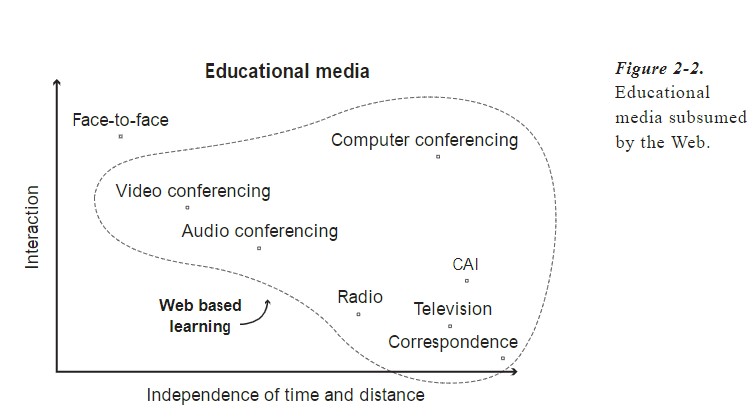

Figure 2-2 shows the capability of the Web to support these modalities. As can be seen, all forms of mediated educational interaction are now supported, assuming one adds the use of the Web to enhance classroom-based education. Thus, the capacity for the Web to support online learning in general is usually too large a domain for meaningful discussion until one specifies the particular modality of interaction in use.

Interaction can also be delineated in terms of the actors participating in it. Michael Moore first discussed the three most common forms of interaction in distance education: student-student, student-teacher, and student-content (Moore, 1989). This list was expanded by Anderson and Garrison (1998) to include teacher-teacher, teacher-content, and content-content interaction. I have been developing an equivalency theorem describing the capacity to substitute one form of interaction for another, based on cost and accessibility factors (Anderson, 2002; Anderson, 2003).

Figure 2-3 illustrates these six types of educational interaction, and each is described briefly below.

-

Student-student Interaction

Traditionally, student-student interaction has been downplayed as a requirement of distance education as a result of constraints on the availability of technology and an earlier bias among distance-education theorists toward individualized learning (Holmberg,1989). Modern constructivist theorists stress the value of peer-to-peer interaction in investigating and developing multiple perspectives. Work on collaborative learning illustrates potential gains in cognitive learning tasks, as well as increases in completion rates and the acquisition of critical social skills in education (Slavin,1995). Work by Damon (1984) and others related to peer tutoring illustrates the benefits to both the tutor and the tutee that can result from a variety of forms of “reciprocal” teaching. Finally, peer interaction is critical to the development of communities of learning (Wenger, McDermott,&Snyder, 2002) that allow learners to develop interpersonal skills, and to investigate tacit knowledge shared by community members as well as a formal curriculum of

studies.

-

Student-teacher Interaction

Student-teacher interaction is supported in online learning in a large number of varieties and formats that include asynchronous and synchronous communication using text, audio, and video. The facility of such communications leads many new teachers to be overwhelmed by the quantity of student communications and by the rise in students’ expectations for immediate responses.

-

Student-content Interaction

Student-content interaction has always been a major component of formal education, even in the form of library study or the reading of textbooks in face-to-face instruction. The Web supports these more passive forms of student-content interaction, and also provides a host of new opportunities, including immersion in microenvironments, exercises in virtual labs, online computer-assisted tutorials, and the development of interactive content that responds to student behavior and attributes (often referred to as“student models”). Eklund (1995) lists some potential advantages of such approaches, noting that they allow instructors to:

•provide an on line or intelligent help facility, if a user is modeled and their path is traced through the information space;

•use an adaptive interface based on several stereotypical user classes to modify the environment to suit individual users; and

•provide adaptive advice, and model the learner’s use of the environment (including navigational use, answers to questions,

and help requested) to make intelligent suggestions about a preferred individualized path through the knowledge base.

To these advantages must be added the capacity for immediate feedback, not only for formal learning guidance, but also for just-in-time learning assistance through job aids and other performance support tools.

-

Teacher-teacher Interaction

Teacher-teacher interaction creates the opportunity for professional development and support that sustains teachers through communities of like-minded colleagues. These interactions also encourage teachers to take advantage of knowledge growth and discovery in their own subject and within the scholarly community of teachers.

-

Teacher-content Interaction

Teacher-content interaction focuses on the creation of content and learning activities by teachers. It allows teachers continuously to monitor and update the content resources and activities that they create for student learning.

-

Content-content Interaction

Content-content interaction is a newly developing mode of educational interaction in which content is programmed to interact with other automated information sources, so as to refresh itself constantly, and to acquire new capabilities. For example, a weather tutorial might take its data from current meteorological servers, creating a learning context that is up-to-date and relevant to the learner’s context. Content-content interaction is also necessary to provide a means of asserting control of rights and facilitating tracking of the use of content by diverse groups of learners and teachers.

-

A Model of E-learning

A first step in theory building often consists of the construction of a model in which the major variables are displayed and the relationships among the variables are schematized. Figure 2-4 provides a model that illustrates the two major modes of online learning. The model illustrates the two major human actors, learners and teachers, and their interactions with each other and with content Learners can of course interact directly with content that they find in multiple formats, and especially on the Web; however, many choose to have their learning sequenced, directed, and evaluated with the assistance of a teacher. This interaction can take place within a community of inquiry, using a variety of Net-based synchronous and asynchronous activities (video, audio, computer conferencing, chats, or virtual world interaction). These environments are particularly rich, and allow for the learning of social skills, the collaborative learning of content, and the development of personal relationships among participants. However, the community binds learners in time, forcing regular sessions or at least group-paced learning. Community models are also, generally,

more expensive, as they suffer from an inability to scale to large numbers of learners. The second model of learning (on the right) illustrates the structured learning tools associated with independent learning. Common tools used in this mode include computer-assisted tutorials, drills, and simulations. Virtual labs, in which students complete simulations of lab experiments, and sophisticated search and retrieval tools are also becoming common instruments for individual learning. Printed texts (now often distributed and read online) have long been used to convey teacher

interpretations and insights in independent study. However, it should also be emphasized that, although engaged in independent study, the student is not alone. Often colleagues in the work place, peers located locally (or distributed, perhaps across the Net), and family members have been shown to be significant sources of support and assistance to independent study learners (Potter, 1998).

Using the online model, then, requires that teachers and designers make crucial decisions at various points. A key decision factor is based on the nature of the learning that is prescribed. Marc Prensky (2000) argues that different learning outcomes are best learned through particular types of learning activities. Prensky asks not, “How do students learn?” but more specifically, “How do they learn what?”Prensky (2000, p. 156) postulates that, in general, we all learn:

•behaviors through imitation, feedback, and practice;

•creativity through playing;

•facts through association, drill, memory, and questions;

•judgment through reviewing cases, asking questions, making choices, and receiving feedback and coaching;

•language through imitation, practice, and immersion;

•observation through viewing examples and receiving feedback;

•procedures through imitation and practice;

•processes through system analysis, deconstruction, and practice;

•systems through discovering principles and undertaking graduated tasks;

•reasoning through puzzles, problems, and examples;

•skills (physical or mental) through imitation, feedback, continuous practice, and increasing challenge;

•speeches or performance roles through memorization, practice, and coaching;

•theories through logic, explanation, and questioning.

Prensky also argues that there are forms and styles of games that can be used, online or offline, to facilitate the learning of each of these skills. I would argue that each of these activities can be accomplished through e-learning, using some combination of online community activities and computer-supported independent-study activities. By tracing the interactions expected and provided for learners through the model, one can plan for and ensure that an appropriate mix of student, teacher, and content interaction is designed for each learning outcome.

-

说说你对在线学习交互及模型的理解

-

分享小组关于在线学习交互的最新研究成果

-

拓展阅读

1.国际视野中的在线交互与网络分析:/public/2022/3/c77b82cc-f762-4a67-b9c7-a733637cf21b.pdf

2.基于交互主题的在线学习知识创造研究:/public/2022/3/f64d2a32-ee0b-418d-96ed-ae30b7016b8f.pdf

3.群体知识图谱建构对在线学习交互的影响研究:/public/2022/3/45b99281-07d4-4635-8507-a0a0413e6c06.pdf

4.在线同步教学中交互的设计与实施:/public/2022/3/d49373e8-cb26-4465-8f6f-79b3c3d7fe04.pdf

5. 在线学习的核心要义与转型路向:/public/2022/3/a5552d0a-bfb6-4b97-82a7-8a76ec7b25fe.pdf

-

-

- 标签:

-

加入的知识群:

.jpg)

学习元评论 (0条)

聪明如你,不妨在这 发表你的看法与心得 ~